Moscow's Mercenary Wars: The Expansion of Russian Private Military Companies

As the United States withdraws its military forces from parts of Africa, the Middle East, and South Asia, Russia is expanding its influence in these and other areas. But instead of deploying conventional Russian soldiers, Moscow has turned to special operations forces, intelligence units, and private military companies (PMCs) like the Wagner Group to do its bidding. Russia’s strategy is straightforward: to undermine U.S. power and increase Moscow’s influence using low-profile, deniable forces like PMCs that can do everything from providing foreign leaders with security to training, advising, and assisting partner security forces.

Moscow’s use of PMCs has exploded in recent years, reflecting lessons learned from earlier deployments, a growing expansionist mindset, and a desire for economic, geopolitical, and military gains. Ukraine served as one of the first proving grounds for PMCs, beginning in 2014. The Russians then refined the model as these private mercenaries worked with local forces in countries such as Syria and Libya. Over time, Moscow expanded the use of PMCs to sub-Saharan Africa, Latin America, and other regions—including countries such as Sudan, the Central African Republic, Mozambique, Madagascar, and Venezuela. PMCs now fill various roles to undermine U.S. influence and support Russia’s expanding geopolitical, military, and economic interests.

With operations suspected or proven in as many as 30 countries across 4 continents and an increasingly refined and adaptable operational model, PMCs are likely to play a significant role in Russian strategic competition for the foreseeable future.

Spread of Russian PMC Activity since 2014

Roles & Missions

Russian Special Forces soldiers from the army's intelligence unit take part in a military drill at a training ground near the village of Mol'kino, Krasnodar region, on July 10, 2015. Photo by SERGEI VENYAVSKY/AFP via Getty Images.

Russian Objectives

PMCs play key roles executing Moscow’s policy objectives and advancing Russian national security interests across the globe. Even though PMCs are technically illegal under Article 13.5 of the Russian Constitution, some of President Vladimir Putin’s closest allies—such as Yevgeny Prigozhin—head Russian PMCs. A core component of Russia’s "hybrid warfare" strategy, PMCs provide the Kremlin a quasi-deniable means through which to pursue Russian objectives, complementing or substituting for more traditional, overt forms of statecraft.

- PMCs provide the Kremlin with a tool to expand Russian influence across the globe. Through the use of PMCs, Moscow can support state and non-state partners, extract resources, influence foreign leaders, and engage in other activities that further Russian foreign policy goals.

- With military skills and capabilities, PMCs enable Moscow to project limited power, strengthen partners, establish new military footholds, and alter the balance of power in out-of-area conflicts toward preferred outcomes while maintaining a degree of plausible deniability for the Kremlin. PMC contractors are also more expendable and less risky than Russian soldiers, particularly if they are killed during combat or training missions.

- Often recruited from Russian military and security forces, PMC operatives build intelligence networks in key theaters to collect insights for Kremlin decisionmakers and conduct intelligence operations, including political influence, covert action, and other clandestine activities.

- PMCs and associated energy, mining, security, and logistics firms provide Moscow a means to expand trade and economic influence in the developing world and build new revenue streams, particularly from oil, gas, and mineral extraction, to reduce the impact of sanctions.

- Typically run by Kremlin-linked oligarchs, PMCs and the lucrative benefits that can accrue from deployments give the Kremlin a lever for balancing competing political and financial interests among oligarchs and exploiting PMCs’ quasi-legal status to ensure loyalty to Putin.

- Moscow leverages even small-scale deployments to enhance global perceptions of Russian power and global influence while propagating pro-Russian narratives in foreign operating environments through PMC-linked media and disinformation outlets.

- PMCs serve as a tool to expand Russian soft power, including themes of "Russian patriotism" and Slavic identity among ideologically minded citizens in the former Soviet states and Balkans.

Training

PMCs conduct training before deploying abroad, including at bases inside Russia and likely with the support of Russian military and intelligence agencies. Russia’s largest and most capable PMC, Wagner Group, conducts training at two camps attached to the location of 10th Special Mission Brigade of GRU Spetsnaz in Mol’kino, Krasnodar region, Russia.

The main base features a headquarters, an airborne training and obstacle course, weapons and munitions storage, and other military facilities.

North of the main military base, Wagner has a separate facility. The Wagner base was likely built between 2015 and 2016, encompasses approximately six acres, and consists of approximately nine permanent structures of varying sizes. Images show numerous and varying numbers of cargo trucks, small trucks, and civilian vehicles.

Features south of the main base include a short-range ballistic missile (SRBM) unit—shown here—as well as an unidentified internal base and other training areas.

Tasks

PMC units conduct a variety of military, security, and information warfare missions in deployments abroad, sometimes augmenting regular Russian forces. PMCs may be specialized for key tasks or serve multiple battlefield roles.- Paramilitary

- PMCs train, equip, assist, and enable host-nation security forces and/or local proxy militias for battlefield operations.

- Combat

- PMC specialists provide key tactical capabilities for specialized tasks, such as sniping, fire support, anti-air, and direct action.

- Intelligence

- Often PMC operatives linked to the Russian intelligence agency GRU recruit human intelligence sources, guide intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) assets, and conduct political warfare, sabotage, and other covert action missions.

- Protective Services

- PMCs provide protective details for senior local government officials, including serving as presidential guards.

- Site Security

- PMCs secure key energy infrastructure, mining, and mineral extraction sites at the behest of host nations as well as for associated Russian companies operating the sites.

- Propaganda and Disinformation

- PMCs and associated media organizations disseminate pro-Russian messages and narratives to key online audiences while also building field organizations such as “patriotic youth camps” on the ground.

Ukraine

PMCs first began operating in Ukraine during Russia's annexation of Crimea in March 2014 before taking on a central role in Moscow's ongoing covert war in Eastern Ukraine's Donbas region. Operating independently or augmenting regular Russian forces, PMC personnel in Ukraine including from Wagner Group reached between 2,500-5,000 during peak of fighting in 2015.

PMCs provided Moscow an ideal tool through which to pursue its geopolitical, military, and ideological objectives in Ukraine: destabilizing then consolidating control over Crimea and Donbas, undermining and pressuring Kyiv and its Western backers for diplomatic concessions, and doing it all while denying any official Russian involvement. However, while PMCs enabled Moscow and its Donbas proxies to seize and secure control over new "independent" republics in Donetsk and Luhansk, their battlefield achievements largely stalled since 2015, rendering the frontlines of Eastern Ukraine another Russian-backed frozen conflict. Moreover, Russian attempts to maintain "plausible deniability" for their actions fooled few Western governments, resulting in sanctions on Kremlin and PMC officials and organizations.

Nonetheless, Russia’s intervention in Ukraine was one of the first battlefield applications of its new "hybrid warfare" doctrine, and Moscow integrated PMCs into its military operations. Russia applied several lessons, such as exploiting the military-like capabilities of PMCs and their official "deniability," to its next major foreign operation: Syria.

PMC combat support to Donbas separatists, particularly from Wagner Group, was decisive in pivotal early battles of the war in Eastern Ukraine from 2014 to 2015.

Click on the map for more information about an event.

Syria

Building off its experience in Ukraine, Russia again turned to PMCs in Syria to help achieve important goals—including stabilizing the Assad regime and countering efforts by the United States and its partners. In addition, PMCs played a crucial role capturing oil fields, refineries, gas plants, and other energy infrastructure from rebels. Russian PMCs played an increasingly direct role in pro-regime combat operations over the course of the Syrian civil war and were often synchronized with Russian economic priorities, including securing key energy infrastructure. PMC personnel in Syria reached up to 1,000-3,000 personnel, including contingents from Wagner Group, Vegacy, E.N.O.T., Vostok Battalion, and other PMCs.

Syria was an important testing ground for the application of a hybrid-PMC deployment model, which is now being exported to other battlegrounds. PMCs acted as a ground force with skill sets similar to Russian Spetsnaz through which Moscow could limit regular Russian military casualties and provide deniability for high-risk Russian actions. PMCs synchronized military advances with economic priorities: capitalizing on ground advances in oil- and gas-rich areas, securing key pipelines, oil fields, refineries, and gas plants to stage future ground advances and draw profits. The Wagner Group’s advance on the Conoco Plant in Dayr az Zawr in February 2018 demonstrates how Moscow used PMCs to take risks in a deniable manner. In this case, Wagner attempted to seize the U.S.- and partner-controlled Conoco gas plant both to secure an economically valuable site and test U.S. resolve.

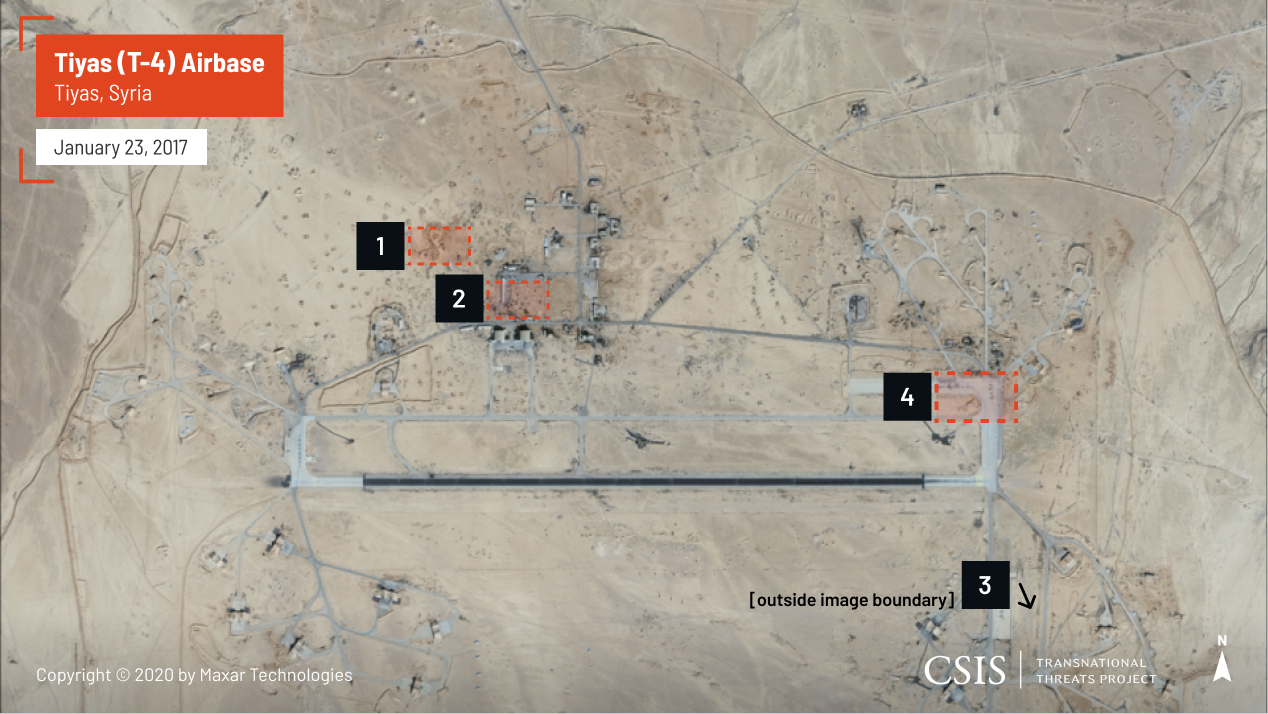

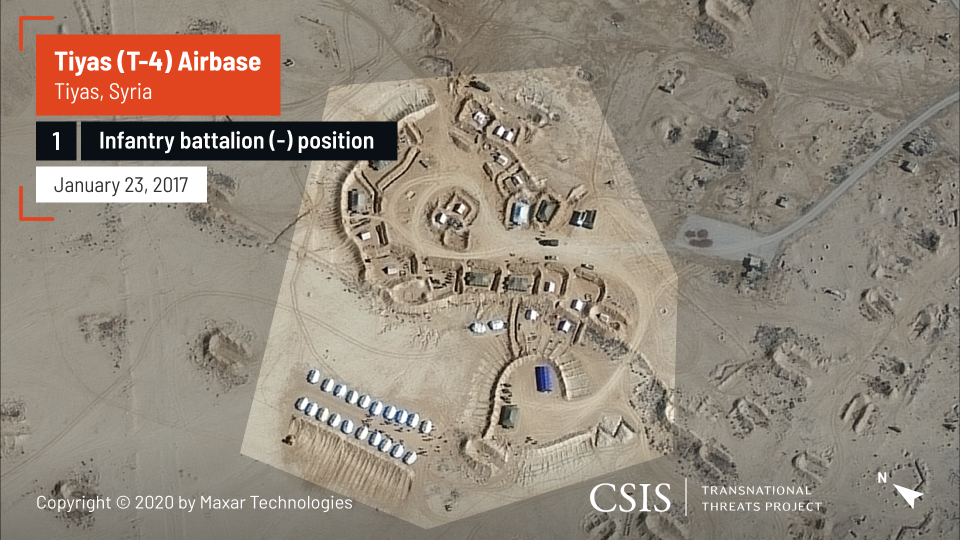

T-4 airbase in central Syria served as a key airbase for Russia in January 2017 as part of its strategy and planning to retake eastern Syria. Battlefield needs in 2017 precipitated a steady increase in specialized ground forces, including Russian PMCs, which led the ground component of this stage of the war. By 2019, Russia had expanded its presence at T-4 to become an all-purpose, air, ground, and intelligence base for its missions in Syria. The following imagery of T-4 identifies possible PMC positions at the airbase in 2017 and 2019.

Full airbase shot of T-4, January 23, 2017.

Left: An infantry battalion position observed at T-4 was likely Russian since the Syrian Arab Army no longer displayed this type of formation six years into the war.

Right: A likely Russian logistics facility at T-4.

A tank company and support element position at T-4. Russia expanded its presence at the airbase since battlefield needs required increased ground forces.

Russian ground attack aircraft, rotary-wing aircraft, and unmanned aerial vehicles in May 2019 indicate Russia’s expanded presence at T-4.

This multi-mission role of PMCs—military, political, economic—and integration into host-nation proxy forces would next be employed in Libya.

Libya

With lessons learned from supporting the Assad regime in Syria, Russia deployed PMCs to Libya's civil war to bolster General Khalifa Haftar, his Libyan National Army (LNA), and the eastern-based government in Tobruk. Since 2017, PMCs such as Wagner Group have been at the vanguard of Russian efforts, advising and enabling Haftar's LNA offensive into western Syria and assault on the UN-backed Government of National Accord (GNA) in Tripoli in 2019. Moscow deployed up to 800-1,200 PMC personnel, primarily from Wagner Group, to multiple training sites, forward bases, and key energy and infrastructure facilities as of early 2020, conducting a variety of missions vital to Haftar's offensive and to Russian interests.

1,600 Russian "Wagner" PMC militants left the west of Libya after the defeat and flight of the Russian-Haftar troops. View original tweet.

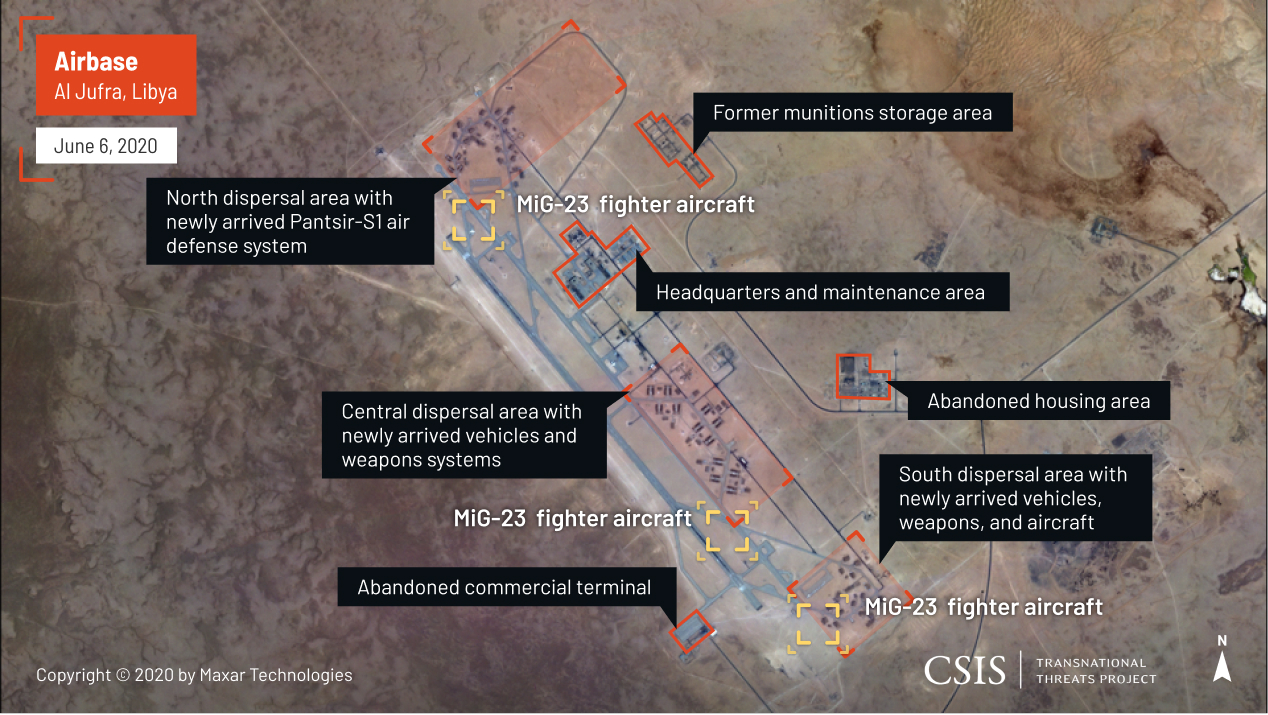

One of Russia’s primary deployment sites has been Al Jufra Air Base in central Libya, which has served as the launching pad for Wagner Group forces and Russian air support to the Tripoli campaign. A close examination of Russia’s deployment at Al Jufra Airbase reveals an expansion of Russian air and ground forces. In particular, satellite imagery shows a growth in the presence of the Russian PMC Wagner Group, a core component of Russia’s intervention in Libya.

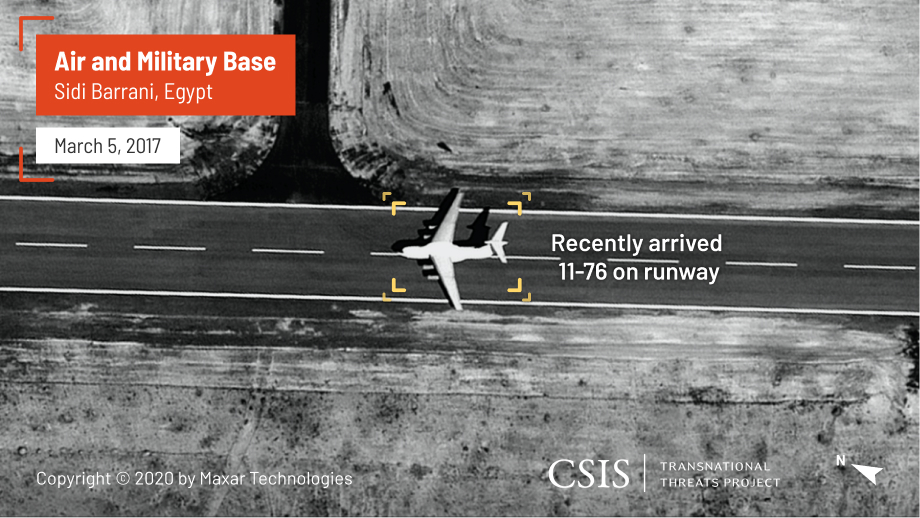

PMCs have been Moscow's spearhead for advancing its foreign policy, military, and economic interests in Libya. With the Libyan civil war, Russia saw a power vacuum and chance to exploit the instability to expand Russian influence, using PMCs to bolster Haftar, tip the conflict in their favor, and reap the rewards. In exchange, Moscow sought economic and military concessions, deploying PMCs to key oil and gas facilities and Mediterranean ports as those areas fell to the LNA. Russia also used Libya to strengthen ties to traditionally U.S. partners, namely UAE and Egypt. Since 2017, Russian PMCs have deployed to Egypt’s Sidi Barrani airfield to direct joint Russian-Egyptian military support to Haftar. Newly acquired CSIS imagery shows the deployment of Russian equipment at Sidi Barrani in March 2017.

Left: A recently arrived Il-76 transport aircraft in March 2017 at Sidi Barrani. Russian special operations forces and private military contractors deployed to Sidi Barrani as part of a bid to support Libyan military commander Khalifa Haftar.

Right: Vehicles on the aircraft apron at Sidi Barrani in March 2017.

Russia's deployment of PMCs to Libya has strengthened its geostrategic position and diplomatic influence in the country, ensuring Moscow's role in any resolution of the conflict and an end-state amenable to Russian interests. However, there were also limits to Moscow’s use of PMCs. Despite assistance from PMCs, the LNA was unable to seize Tripoli and even triggered an expanding intervention from Turkey to bolster the GNA. Wagner Group alone has lost hundreds of fighters and key weapons systems in Tripoli's heavy ground fighting and from Turkish drone strikes. Nonetheless, through its PMC-led intervention, Moscow has gained a new strategic foothold and geostrategic position on the Mediterranean, as well as a bridgehead into the rest of the African continent.

Sub-Saharan Africa

Though Russian PMCs first appeared in the Democratic Republic of the Congo as early as 2014, Russia significantly expanded the geographic scope and missions of PMCs in Sub-Saharan Africa following its interventions in Ukraine, Syria, and Libya. Russia has primarily used PMCs to target resource-rich countries with weak governance, such as Sudan, the Central African Republic, Mozambique, and Madagascar. Though PMC tasks have varied from case to case to meet local needs, in each of these countries Russia exchanged military and security support for economic gains and political influence.

Sudan

In Sudan, Russia used Wagner Group to provide military and political support to President Omar al-Bashir in exchange for gold mining concessions. Russia also had a strategic motive to seek basing rights in the Red Sea. In November 2017, Moscow facilitated a mining operations agreement for M Invest, a Russian company tied to Yevgeny Prigozhin. PMC troops, who arrived the following month, provided training and military assistance to local forces. In addition, PMCs orchestrated a disinformation campaign to discredit protesters through many of the same techniques the Internet Research Agency, linked to Prigozhin, used in the 2016 U.S. presidential election.

Central African

Republic

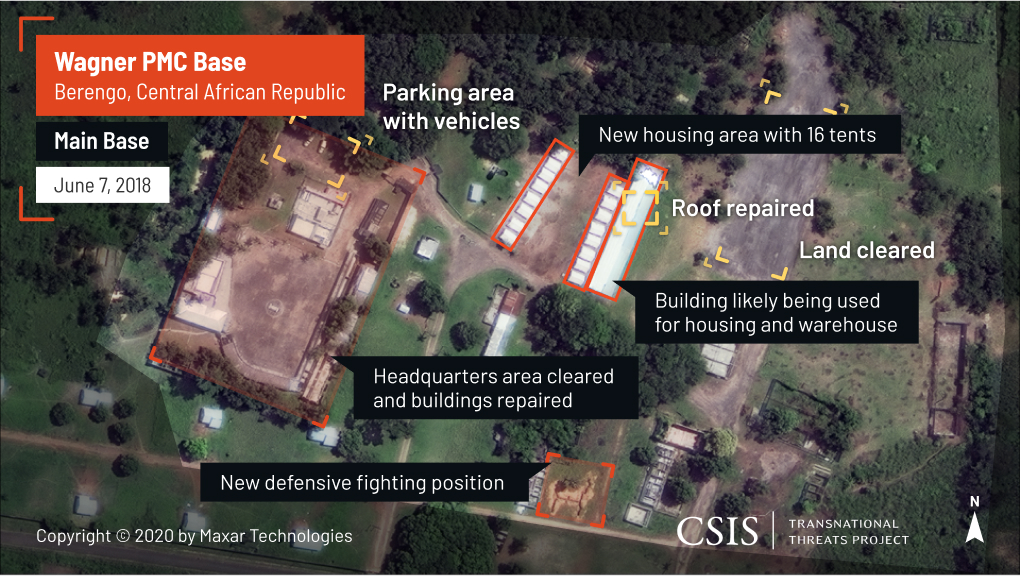

Russia has followed a similar model in the Central African Republic, where the Wagner Group and Patriot—another Russian PMC—have reportedly been active. Beginning in January 2018, Russia exchanged military training and security—primarily for President Faustin-Archange Touadéra and mining operations—for access to gold, uranium, and diamonds. New CSIS imagery sheds light on the training camp these troops established southwest of Bangui in the ruins of the Palace of Berengo.

Madagascar

In early spring 2018, Wagner Group sent a small group of political analysts to Madagascar to support incumbent President Hery Rajaonarimampianina's reelection bid in exchange for economic agreements on mining (chromite and gold), oil, agriculture, and the port of Toamasina. In April, additional troops arrived to provide security and military training, allegedly with the assistance of Federal Security Service and GRU officers. Though Rajaonarimampianina lost the election, he facilitated the promised agreements prior to leaving office. Ferrum Mining, a Russian company involved in one such deal, began operations on the island in October 2018 but soon paused due to strikes.

Mozambique

In Mozambique, Russia traded Wagner's military support against Islamist insurgents in Cabo Delgado province for access to natural gas. Wagner troops arrived in early September 2019 but were unprepared for the mission. They had little experience conducting operations in the brush and difficulty coordinating with local forces. After significant losses, Wagner troops retreated south to Nacala in November 2019 to regroup. Despite sending additional equipment and troops in February and March 2020, Wagner was replaced in April by the Dyck Advisory Group, a South African PMC. It is unclear whether any Wagner troops remain in the country.

Latin America

Russia’s global use of PMCs has also extended to Latin America, though they are not as widespread as in Africa. PMCs have most notably played a role in Venezuela, though their presence has also been rumored in countries such as Nicaragua.

Venezuela

PMCs have been present in Venezuela since at least 2017 to guard Russian business interests and companies, such as Rosneft. Despite investments in the Venezuelan economy, Moscow's relationship with Caracas is primarily driven by a geostrategic desire to reassert its influence in the region at the expense of the United States. In response to the Trump administration's calling for the ouster for Venezuelan leader Nicolás Maduro and recognition of opposition leader Juan Guaidó as interim president in January 2019, Russia deployed approximately 100 security contractors, likely from Wagner, the same month to provide security to president Maduro amid political upheaval. These contractors conducted surveillance and cybersecurity protection in addition to physical security.

Outlook & Implications

August 4, 2018: Victor Tokmakov, first secretary of the Russian Embassy, presents diplomas to graduating recruits in Berengo. Russian military consultants have set up training for the Central African Armed Forces and the Internal Security Forces after delivering weapons to the country. Photo by FLORENT VERGNES/AFP via Getty Images

These examples demonstrate Russia’s expanding global use of the PMC model to advance its geopolitical and economic goals and undermine U.S. interests. PMCs provide the Kremlin a deniable means to project power and influence into its "near-abroad," as recent PMC activity in Belarus has demonstrated. They offer a glimpse of how Russia plans to compete with the United States in the future, particularly in weak, strategically located, and resource-rich states.

PMCs are an important instrument in a broad Russian toolkit that includes covert action, cyber operations, and other irregular activity across the globe. Yet PMC activities have not always been successful. In Libya, for example, Russia and its PMCs suffered a serious setback following the battlefield losses of Khalifa Haftar. Despite such problems, U.S. efforts to counter Russian PMCs have been weak and ad hoc. A more effective response should include several steps.

- The first is publicly highlighting what Russian PMCs are doing, where they are operating, and how they are connected to the Russian government—including to President Putin and others in the Kremlin. This analysis provides important details of the scope and activities of PMCs.

- A second step is to highlight and exploit Russia’s challenges with PMCs. Many are ineffective, corrupt, and engaged in human rights abuses. In the end, Moscow’s use of PMCs may actually undermine Russian influence rather than improve it. While PMCs have enabled Russia to shape conflict trajectories, gain influence in key theaters, and win military and economic concessions, there are limits to what PMCs can achieve. They have been most effective when deployed for limited or specific objectives, such as bolstering Syrian forces, aiding Donbas separatists in Ukraine, or gaining favor in the Central African Republic and Sudan. By themselves, however, PMCs are rarely decisive in winning conflicts, particularly when faced with capable and committed opponents or operating in unfamiliar terrain.